Market Size vs. Market Power

Photo by Jaime Spaniol on Unsplash

It’s widely accepted in Startupland that you should only attack very large markets. Of course size is a factor of both spend and growth rate, but the end result should be several billion dollars of addressable value in relative short order. It’s for this reason that many founders feel obligated to build mind-numbing slides of nesting TAM, SAM, SOM ovals. Whoever thought up these acronyms, even if still alive and well, is dead inside…

What’s much less discussed is the importance of market power. Power within a dynamic market is an abstract concept that can be cut and copied in several ways. There’s no shortage conceptual frameworks available to founders today; from business school classics, to overhyped books to quite entertaining creative content. But these all feel a little over-complicated or self-indulgent.

An old boss once taught me that the easiest way to find truth is force binary extremes, pick a side and then loosen the framework to a gradient. This is how I evaluate market power and why I focus where I do.

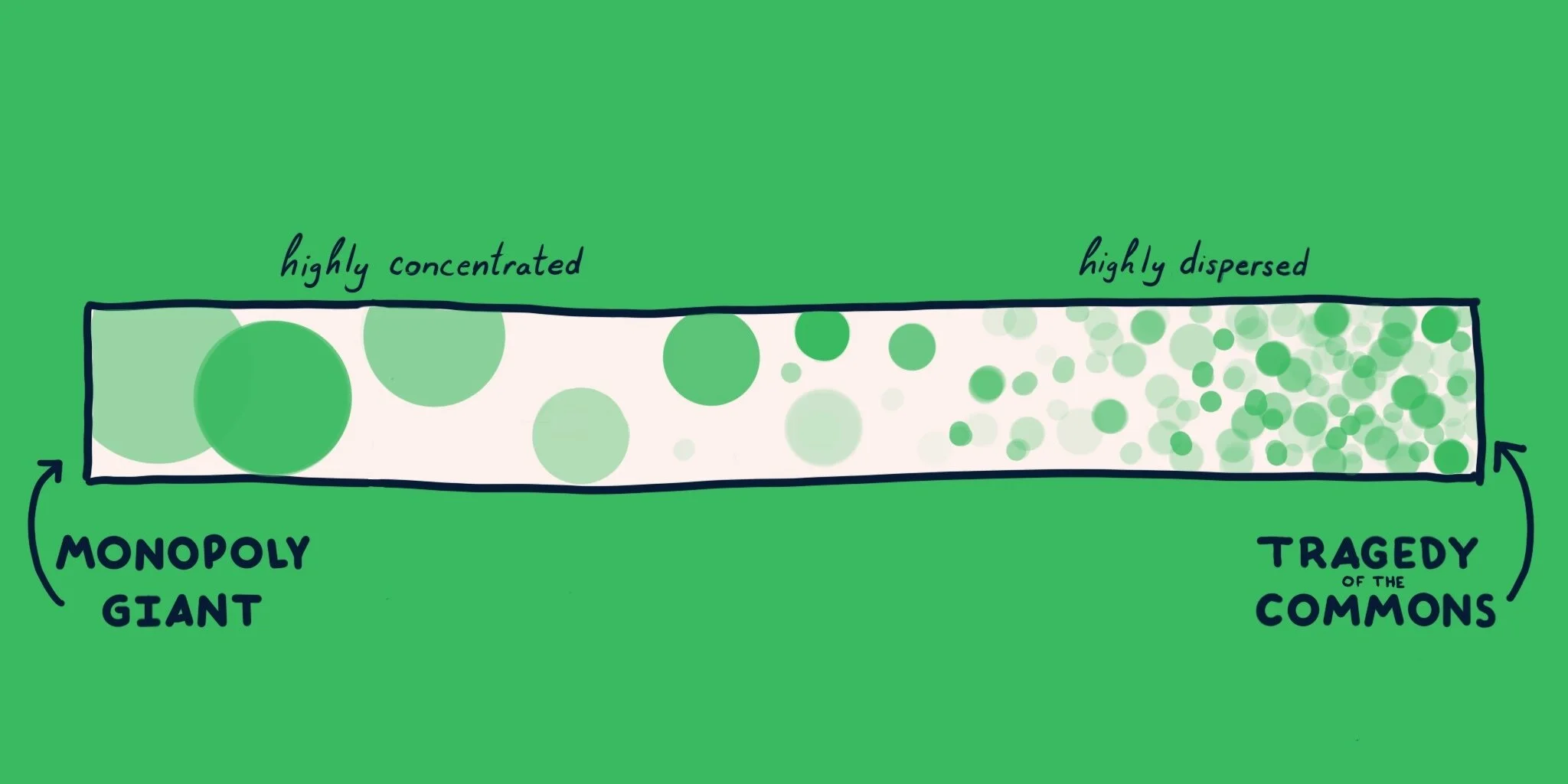

Each bubble in the graphic above represents a relative market (i.e. consumer fire insurance, pen testing security, online ad attribution, etc.) where the size reflects that degree of fragmentation and (thus power) you’re subjected to. The actual size is determined through a simple division of market size / # of potential customers. Based on this we would expect credit scoring services to fall on the left and accounting services to fall on the right. The key tradeoff that I see many founders fail to appreciate is leverage vs. cost. Too consolidated and you’re quickly at the mercy of your customers but too fragmented and you can’t scale.

Monopoly Giant

At one extreme end you may have all purchasing taking place within a single organization. These are usually terrible markets to sell into because there is very little interest or need to innovate. When “innovation” does take hold it’s typically through existing incumbent relationships. Only the heavy handed regulation or paradigm shift technical advancement can break through. Defense or aerospace are the clearest examples of this. Yes you can build a nice business, but if you can fit all of your potential customers on a single notecard, they’re going to be setting the plans / agenda / pricing, not you.

Tragedy of the Commons

At the other extreme you find a large problem / spend in aggregate, but only in aggregate. The pain point is so diffused amongst the population that no one person ever really cares enough. This is a challenge that many sustainability startups have struggled with in the past. Fortunately that’s changing, but mostly due to new regulation which focuses the pain on individual entities like carbon taxes. The most common example I’ve seen here is with startups that serve the NHS (UK national healthcare). A system-level savings argument sounds fantastic but almost always breaks at the practice level because the cost / time / etc. is too diffused for any physician to care..

Highly Concentrated

Most founders face markets with slightly less extreme power dynamics but many don’t fully appreciate the embedded risks that comes with imbalanced market power. Large spends are shared by just a handful of industry giants. An account here can be massive and their established distribution can really accelerate a startup. As an enterprise-focused investor you would think I would like this area, but I actually think oligopoly markets are a trap. These big players are happy to dole out some serious cash for pilots / trials but when conversion conversations start they show their true colors. Exclusivity and forced “strategic” investments are are not common, but the larger concern is a ceiling to revenue potential. I’ve seen this most frequently in the AI for drug discovery wave. A lot of promising startups were able to gain early traction but hit a wall. With only so many available customers many are forced to drastically pivot into compound development (a VERY different business) or take an early acquisition.

Highly Dispersed

Market spend is spread amongst a very large volume (tens of thousands in some cases). Account values are drastically lower but the high volume user base unlocks the true scalability of software distribution. Examples are plentiful and SaaS strategies even more so (see Jason Lemkin). At this level founders face a sort of reverse leverage where customers can’t wield power on you but they can (typically) just walk away. The benefits of switching costs and relationship inertia fall away and are replaced with the challenges of acquisition efficiency, churn and a generally more fickle customer base. As long as pain points are concentrated enough you can find buyers but you’ll need a product unique / delightful / sticky enough to keep them.

Personally I like to play somewhere in the middle of this gradient with large markets being comprised of a few hundred potential customers. This segment tends to feature more complex go-to-market components, which is a strength of mine so in theory I have an investing advantage here (jury’s still out). The key thing that separates good from great investments are founders who can identify and articulate the leverage. Halo-effect clients, champion / challenger supply models and metadata lock-in are some of my favorites, but of course the best part of venture if continously learning new ones. If you’re a founder building a B2B startup that’s playing off a unique leverage point I would love to hear from you.